Wednesday, August 13, 2025

This morning, we enjoyed a bit of leisure time to allow our fellow WolfTrekkers—who arrived late last night—to recover from their flights. I took the opportunity to relax in the room and catch up on news from home, while Jane opted for a more active start to the day. She headed to the hotel fitness center, ran on the treadmill for about 30 minutes, and followed it with a 15-minute cool-down walk. She returned refreshed and energized, and after a quick shower, we made our way down to the restaurant for breakfast.

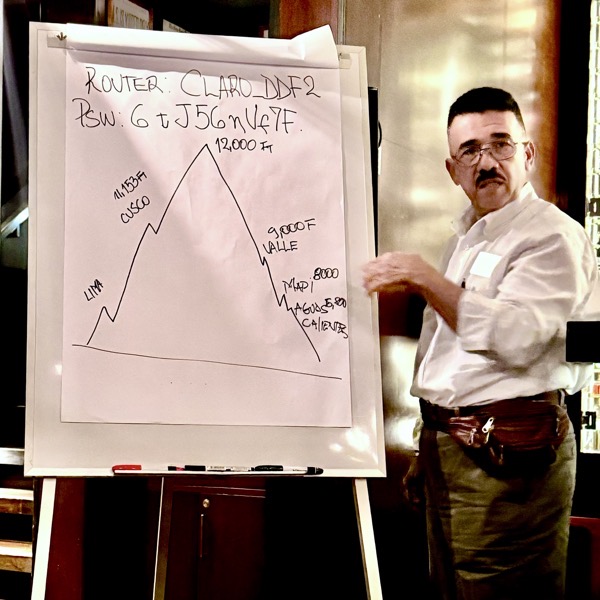

At 10:45 a.m., our Odysseys tour director, Victor, gathered the now-expanded WolfTrekkers group—grown from five to thirteen travelers—for an orientation session in a private bar of the hotel. He gave us an overview of the Peruvian segment of our journey, shared general travel information, and outlined the rest of the day’s itinerary. We also received our personal audio devices (“whisper” or “vox” systems), which we’ll use during walking tours to hear our guides more clearly. Victor also asked us to select our meal preferences for three upcoming group dinners from menus he provided.

Orientation with Odysseys Guide, Victor

Orientation with Odysseys Guide, Victor

Lunch wasn’t included today, so we grabbed a light snack on our own before boarding the bus in the early afternoon for a guided tour of this historic capital city. Originally founded by the famed Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro, Lima has evolved into one of the largest and most influential cities in the Americas. Today, it is home to nearly one-third of Peru’s population (over 10 million people) and serves as the country’s political, cultural, and economic heart. Unfortunately, we only have an afternoon to explore Lima’s rich tapestry of colonial architecture, world-class museums, prestigious universities, and significant religious landmarks.

As we departed, we noticed that the sky still wore the same pale, whitish gloom we had seen upon our arrival five days earlier. This phenomenon, known as the garúa, is a dense, persistent marine layer of fog and low clouds that blankets Peru’s coast in winter, caused by the cold Humboldt Current cooling the air above it. Under the bleak skies, the infamous Lima traffic remained in full force, though we seemed to move a bit less slow than during last night’s rush hour.

Eventually, we were dropped into the bustling heart of Lima. Slipping on our earphones, we followed Victor as he guided us through Plaza San Martín, where a towering equestrian statue of its namesake, José de San Martín, commands the center—a tribute to the Argentine general who led Peru to independence from Spain in 1821.

Plaza San Martin

Plaza San Martin

After walking through Plaza San Martín, we continued to follow Victor down a lively, bustling street and eventually emerged into another grand square—Plaza Mayor, also known as Plaza de Armas. We had arrived at Lima’s historic birthplace, a majestic colonial plaza framed by monumental landmarks: the Cathedral of Lima, the Government Palace, the Archbishop’s Palace, and the Municipal Palace (City Hall). This square marks the exact spot where Francisco Pizarro founded the city on January 18, 1535. With its elegant symmetry, palm-lined gardens, and layers of political and religious history, Plaza Mayor remains the ceremonial and symbolic heart of Peru. We gazed in awe at both the architecture and the people around us, as Victor vividly recounted the square’s storied past and described the magnificent edifices that surrounded us.

—— Plaza Mayor (a.k.a Plaza de Armas) ——

We exited Plaza Mayor along a street diagonal from the corner where we had first entered, and before long, Victor paused in front of a charming Republican-era building with an ornate façade, arched windows, and an elegant clock tower. This was the former Lima Post Office—Casa de Correos y Telégrafos. Victor fondly reminisced about mailing letters there in days gone by. Today, the building houses a postal museum and cultural exhibits, preserving the history of communication in Peru.

Just a short walk from the post office, we stopped in front of another remarkable landmark: Casa de Aliaga. Built in 1535 by Jerónimo de Aliaga, a Spanish conquistador and close ally of Francisco Pizarro, it is one of the oldest continuously inhabited colonial mansions in the Americas. Incredibly, the house has remained in the Aliaga family for over 17 generations, a living testament to Lima’s layered colonial and aristocratic past.

Old Lima Post Office

Old Lima Post Office

Aliaga House

Aliaga House

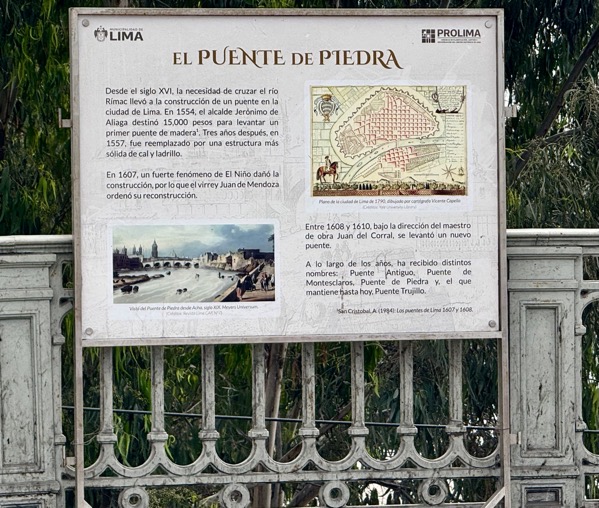

We continued following Victor and arrived at the Stone Bridge (El Puente de Piedra), a historic landmark that marks the edge of Lima’s colonial center. From this arched stone span, built in 1610, we looked out over the valley of the narrow, low-running Rímac River, its banks edged by concrete and time. In the distance, Cerro San Cristóbal rose into view, its slopes dotted with colorful homes clinging to the hillside. Just beyond the bridge, we caught sight of ongoing archaeological excavations, where layers of Lima’s pre-Hispanic past were being unearthed, offering glimpses into a city far older than its colonial heart.

—— The Stone Bridge (El Puente de Piedra) ——

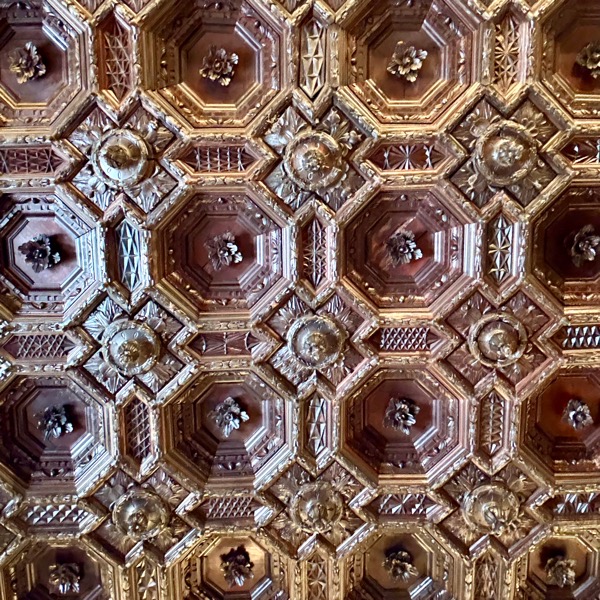

From the bridge, Victor led us back into Lima’s historic center to the Museo del Convento Santo Domingo, part of a grand 16th-century Dominican complex—one of the oldest and most important religious institutions in Peru. The convent museum features baroque architecture, intricately carved dark wood ceilings, and a stunning tiled cloister lined with Sevillian azulejos from the 1600s.

—— Santo Domingo Convent ——

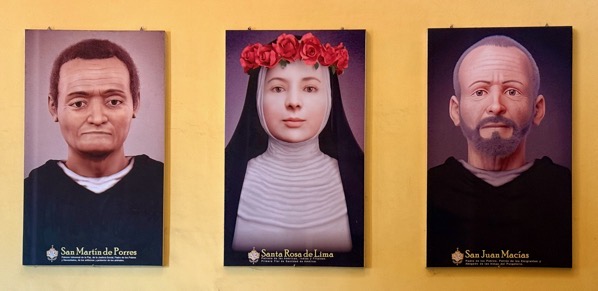

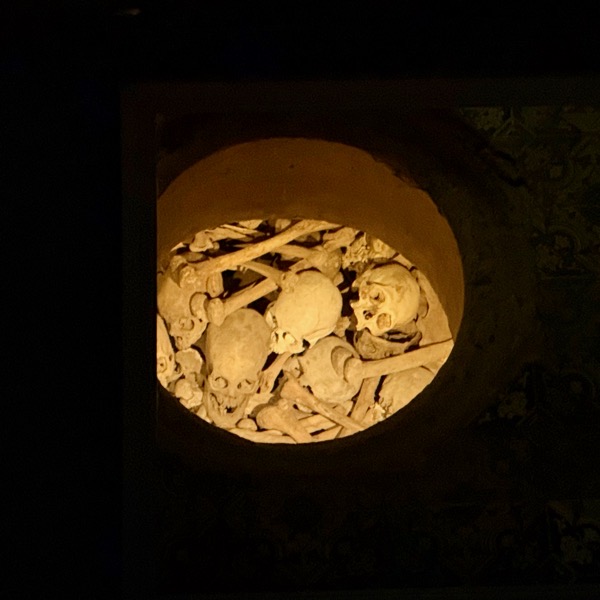

From the cloister, we followed Victor down a stairwell into a chapel honoring three revered Peruvian saints: Rose of Lima, Martin de Porres, and Juan Macías. We then stepped into a solemn, dimly lit crypt where Saint Rose of Lima’s remains were once interred. The crypt, with its simple stone walls, devotional niches, and votive offerings, preserves an atmosphere of deep reverence—serving as a place of quiet pilgrimage, and still holding the relics of Saints Martin and Juan, whose legacies of humility and compassion continue to draw the faithful.

—— Saint Rose of Lima Crypt ——

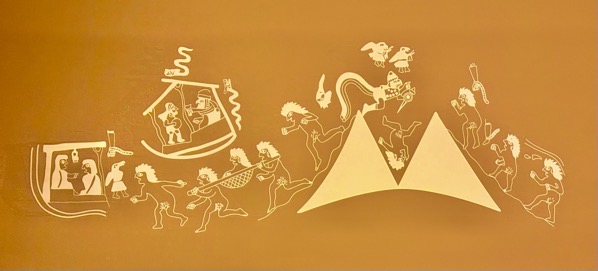

We ascended the stairs, and Victor narrated as we passed through an impressive gallery of 17th- and 18th-century religious art. The walls were lined with large oil paintings depicting scenes from the lives of Dominican saints, the Passion of Christ, and the Virgin Mary—each framed in ornate gold leaf, their colors still vibrant despite the centuries. Victor paused to spend some time describing a striking 1867 painting titled “The Funeral of Atahualpa”. The canvas portrayed a somber yet theatrical scene of the last Inca emperor’s body being mourned by indigenous nobles and Spanish friars, set against the backdrop of colonial conquest and religious ritual. Rich in symbolic detail and historical tension, the painting serves as a powerful commentary on the collision of two worlds—Inca and Spanish—that defines Peru’s colonial legacy.

We then visited the convent library, a remarkable space that felt suspended in time. Lined with towering cedar shelves, it houses over 25,000 antique volumes, including leather-bound theological texts, illuminated manuscripts, and early scientific works written in Latin, Spanish, and Quechua. The high coffered wooden ceiling, the scent of old paper and polished wood, and the filtered light streaming through arched windows created an atmosphere of quiet reverence. This was enhanced by stage mannequins dressed in traditional Dominican robes, positioned throughout the room, which brought to life the scholarly monks who once studied and prayed here.

—— Santo Domingo Art Gallery and Library ——

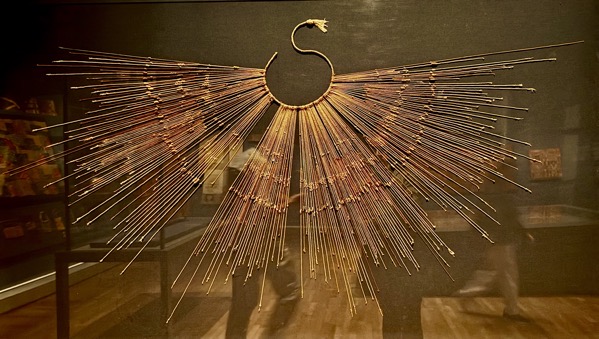

After exiting the Santo Domingo Convent, we walked a short distance to board the tour bus that took us to the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI). Victor guided us through an impressive collection, spotlighting exquisite pre-Columbian artifacts such as ancient pottery, stoneware, intricate tapestries, finely woven textiles, and fascinating quipus—the knotted string devices used by Andean cultures for record-keeping and communication. The museum was truly superb! On our own, Jane and I could have easily spent hours—at least half a day—exploring the vast array of works spanning over 3,000 years of Peruvian history, from early civilizations all the way to contemporary art. Unfortunately, our time was limited by the tour schedule, and we departed far too soon, hopeful that we could return someday for a deeper dive.

—— Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) ——

We returned by bus to the Westin Lima Hotel, where we later gathered with our fellow WolfTrekkers for a warm and welcoming group dinner in the hotel’s elegant restaurant. It was a relaxing way to unwind, share impressions from the day, and connect with others on the journey ahead. After dinner, we headed up to our room to prepare for tomorrow’s early departure to Cusco, organizing our gear and checking over the essentials. With excitement building for the highlands, we turned in early to rest up for the next leg of our adventure.

—— End of the Day ——